Bleeding – perimenopausal, postmenopausal and breakthrough bleeding on MHT/HRT

Key points

|

![]() Bleeding – perimenopausal, postmenopausal and breakthrough bleeding on MHT/HRT247.86 KB

Bleeding – perimenopausal, postmenopausal and breakthrough bleeding on MHT/HRT247.86 KB

Perimenopausal bleeding

In the menopausal transition, hormonal fluxes may be erratic with vaginal bleeding being both ovulatory or non-ovulatory, light or heavy, reasonably regular or entirely irregular (1). For women considering menopausal hormone therapy (MHT), abnormal bleeding should be investigated before prescribing. Heavy menstrual bleeding, rather than irregular bleeding itself is a hallmark of abnormal build-up of the endometrium. Heavy bleeding after a prolonged interval without bleeding, or prolonged bleeding of any amount should be investigated. A lower investigative threshold should apply for high-risk women.

Postmenopausal bleeding

Postmenopausal bleeding (PMB) refers to any vaginal bleeding that occurs in a menopausal woman ie. 12 months after their final menstrual period. This does not include the regular withdrawal bleed that occurs on MHT.

Any postmenopausal bleeding requires investigation to exclude a sinister cause. The likelihood of endometrial carcinoma for a woman presenting with PMB is 10% (2). However, around 95% of women with endometrial malignancy will present with PMB (3). Risk factors for endometrial cancer include age, obesity, use of unopposed oestrogen, polycystic ovary syndrome, Type 2 diabetes mellitus, atypical glandular cells on screening cervical cytology and family history of gynaecologic malignancy(4). Nulliparity is also a risk factor. Patients taking non-conventional MHT, such as troches and transdermal progestogen are at risk of endometrial hyperplasia and cancer (5).

Women on menopausal hormone therapy

In women taking cyclical MHT, a withdrawal bleed is expected and the patient should be counselled as such. The withdrawal bleed should occur toward the end of, or after the progestogen containing phase of the cyclical regimen. Bleeding which is unpredictable, occurring outside the expected time, or excessively heavy should be investigated.

For women taking continuous combined MHT (CCMHT), the significance of breakthrough bleeding depends upon the recency of her LMP and on how long she has been taking CCMHT. Women within 12 months of the last natural menstrual period often do not achieve amenorrhoea, presumably because some residual endogenously oestrogen-stimulated endometrium is present. Unpredictable breakthrough bleeding is common in this situation and does not need investigation, unless it is unusually heavy. To avoid this, it is recommended that cyclical MHT be used for the first 12 months at least following the LMP. A similar diagnostic and therapeutic approach applies to tibolone.

Bleeding should be investigated if it occurs after six months use of CCMHT or tibolone, or starts after amenorrhoea has been established on this regimen. Amenorrhoea in this setting depends upon the balance between the oestrogenic effect and progestogenic effect of the MHT components on the endometrium. Oestrogen stimulation of the endometrium causes proliferative histological features and progesterone secretory. Inadequate progestogenic effect can therefore result in endometrial proliferation and possibly hyperplasia and bleeding. It may, like unopposed oestrogen therapy, lead to endometrial malignancy. However, more commonly in women taking pharmaceutical preparations of CCMHT, excessive progestogenic effect may produce bleeding from an atrophic endometrium.

Diagnostic evaluation of postmenopausal bleeding (PMB)

The primary goal of investigation is to exclude malignancy, and secondarily to elucidate a treatable non-malignant cause (6).

A detailed history should be taken:

- When does the bleeding occur?

- Is it post-coital?

- What medications is the patient taking eg. anticoagulants, herbal therapies, tamoxifen

- Is the patient taking so-called “bioidentical” hormones?

- Has the patient missed MHT doses?

- When was the last cervical screening test?

- Are there any bladder or bowel symptoms?

Physical examination should include inspection of the vulva, vagina and the cervix for visual evidence of lesions or bleeding, taking note of any signs of atrophy. Bleeding from the perineum, urethra and anus is also a possibility. A cervical co-test (HPV test and liquid based cytology) or cervical smear should be done.

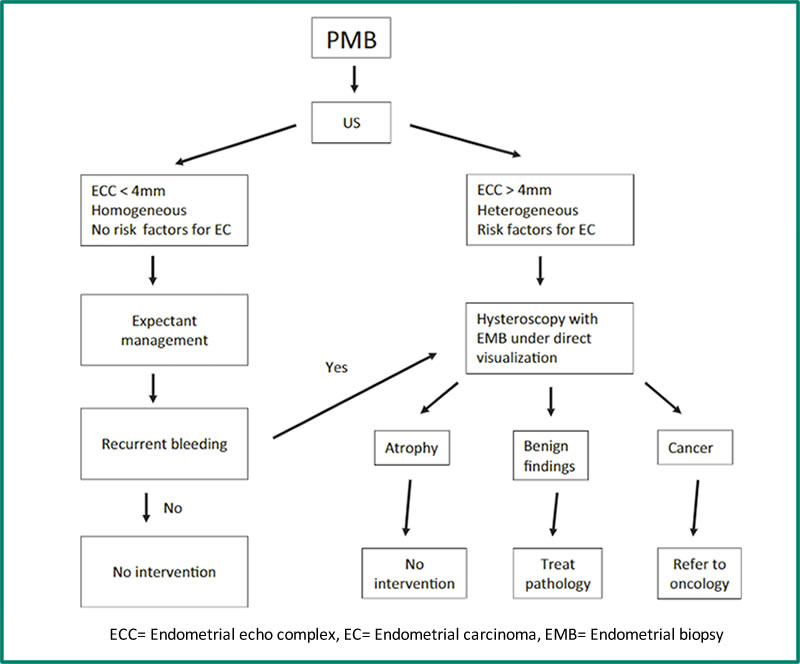

Endometrial ultrasound

Endometrial ultrasound is the initial investigation of choice. This should be done by an experienced specialist gynaecological ultrasonographer and with transvaginal ultrasound (TVUS). In women taking cyclical MHT, it should be done immediately after the withdrawal bleed (7). The ultrasound should be able to identify any localised uterine lesion which may contribute to bleeding – endometrial polyp, submucosal fibroid, hyperplasia or cancer. The significance of PMB for the risk of malignancy differs with use of MHT and endometrial thickness on TVUS. Subsequent investigations depend on the ultrasound findings, so the experience of the ultrasonographer is critical. After excluding localised lesions, the following algorithm is useful (8). Note that this algorithm does not apply to women taking tamoxifen.

Figure 1. Management algorithm for patients with post-menopausal bleeding (8). ECC= Endometrial echo complex, EC= Endometrial carcinoma, EMB= Endometrial biopsy

Tamoxifen therapy

Tamoxifen therapy is associated with stimulation of the endometrium and an increased risk of endometrial cancer (9). Tamoxifen therapy invariably produces a thickened appearance to the endometrium which is not always indicative of neoplasia. Therefore, TVUS is not useful for the investigation of PMB in a woman on tamoxifen therapy and examination of the uterine cavity by hysteroscopy is recommended (6).

Histological assessment

There has been some debate for what is regarded as the upper limit of normal endometrial thickness. Many groups have recently used a cut-off of 4mm (4,10,11). An endometrial thickness of ≤4mm has a 99% negative predictive value for malignancy (4).

Endometrial biopsy should be performed in women who meet the following criteria(4):

- Endometrial thickness >4mm

- Not easy display of the endometrium eg. fibroids

- Persistent PMB

- Suspicion of polyp or mass on transvaginal ultrasound

- Endometrial thickness ≥ 3mm with fluid in the endometrial cavity

Blind tissue sampling such as Pipelle or D&C may be sufficient for pathology that affects the entire endometrial surface, but it is inadequate for detecting localised lesions such as endometrial polyps, which may be malignant (6). Hysteroscopy is superior to endometrial biopsy and ultrasonography for the identification of these structural lesions and is recommended.

Management

Medical management

When a localised or neoplastic lesion is found, the management is surgical. However, when the findings are benign and the patient is taking MHT, some modification of the MHT dose or regimen is required. While there is an abundance of literature about the incidence of bleeding on MHT and the histological findings, there are no evidence-based recommendations guiding therapeutic intervention. Therefore, the following recommendations are based on clinical practice advice from the literature and based on the patterns of histology seen in women with breakthrough bleeding (12-15). They are made here with the proviso that continued bleeding should prompt re-investigation, as above.

a) Cyclical MHT with unpredictable bleeding and negative histological screen for pathology

This may respond to a change in the progestogen component of the MHT such as altering the dose, type of progestogen or the mode of delivery eg. intrauterine.

b) CCMHT with breakthrough bleeding, endometrium >4mm and negative histology

If less than 12 months post LMP, change to cyclical MHT or intrauterine progestogen. If more than 12 months post LMP, change oestrogen/progestogen balance by reducing oestrogen or changing progestogen dose, type or delivery.

c) CCMHT with breakthrough bleeding, endometrium <4mm

This is the most difficult scenario to manage, especially in a patient who wants to have no withdrawal bleeding. The TVUS suggests adequate, if not excessive, progestogenic effect, especially if tissue sampling demonstrates an atrophic sample. Increasing the dose or changing the progestogen formulation does not always address the underlying problem. Continuous progestogen effect on the endometrium exposes superficial dilated blood vessels which predispose to bleeding (16). The same may occur with prolonged tibolone therapy. A change back to cyclical MHT, at least for a while, is recommended or an increase in the oestrogen dose may be effective.

Surgical management

Surgical management is appropriate for neoplastic and local lesions causing bleeding. However, women who have heavy or unmanageable breakthrough bleeding in the absence of pathology, may prefer to have a hysterectomy, after which they need take only oestrogen as MHT. The alternative is endometrial ablation. This may resolve the PMB but it should be noted that progestogen is still necessary since there will be residual endometrium left. Moreover, the above investigations – TVUS, hysteroscopy, endometrial sampling - will be difficult if there is subsequent PMB (17).

References

- Hale GE, Hughes CL, Burger HG, Robertson DM, Fraser IS. Atypical estradiol secretion and ovulation patterns caused by luteal out-of-phase (LOOP) events underlying irregular ovulatory menstrual cycles in the menopausal transition. Menopause. 2009;16(1):50-9.

- van Hanegem N, Breijer MC, Khan KS, Clark TJ, Burger MP, Mol BW, et al. Diagnostic evaluation of the endometrium in postmenopausal bleeding: an evidence-based approach. Maturitas. 2011;68(2):155-64.

- van Hanegem N, Prins MM, Bongers MY, Opmeer BC, Sahota DS, Mol BW, et al. The accuracy of endometrial sampling in women with postmenopausal bleeding: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2016;197:147-55.

- ACOG Committee Opinion No. 734: The Role of Transvaginal Ultrasonography in Evaluating the Endometrium of Women With Postmenopausal Bleeding. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;131(5):e124-e9.

- Eden JA, Hacker NF, Fortune M. Three cases of endometrial cancer associated with "bioidentical" hormone replacement therapy. Med J Aust. 2007;187(4):244-5.

- Munro MG, Southern California Permanente Medical Group's Abnormal Uterine Bleeding Working G. Investigation of women with postmenopausal uterine bleeding: clinical practice recommendations. Perm J. 2014;18(1):55-70.

- Affinito P, Palomba S, Sammartino A, Bonifacio M, Nappi C. Ultrasonographic endometrial monitoring during continuous-sequential hormonal replacement therapy regimen in postmenopausal women. Maturitas. 2001;39(3):239-44.

- Carugno J. Clinical management of vaginal bleeding in postmenopausal women. Climacteric. 2020;23(4):343-9.

- Mourits MJ, De Vries EG, Willemse PH, Ten Hoor KA, Hollema H, Van der Zee AG. Tamoxifen treatment and gynecologic side effects: a review. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;97(5 Pt 2):855-66.

- Saccardi C, Spagnol G, Bonaldo G, Marchetti M, Tozzi R, Noventa M. New Light on Endometrial Thickness as a Risk Factor of Cancer: What Do Clinicians Need to Know? Cancer Manag Res. 2022;14:1331-40.

- Papakonstantinou E, Adonakis G. Management of pre-, peri-, and post-menopausal abnormal uterine bleeding: When to perform endometrial sampling? Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2022;158(2):252-9.

- Stuenkel CA, Davis SR, Gompel A, Lumsden MA, Murad MH, Pinkerton JV, et al. Treatment of Symptoms of the Menopause: An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100(11):3975-4011.

- de Medeiros SF, Yamamoto MM, Barbosa JS. Abnormal bleeding during menopause hormone therapy: insights for clinical management. Clin Med Insights Womens Health. 2013;6:13-24.

- Spencer CP, Cooper AJ, Whitehead MI. Management of abnormal bleeding in women receiving hormone replacement therapy. BMJ. 1997;315(7099):37-42.

- Hillard TC, Siddle NC, Whitehead MI, Fraser DI, Pryse-Davies J. Continuous combined conjugated equine estrogen-progestogen therapy: effects of medroxyprogesterone acetate and norethindrone acetate on bleeding patterns and endometrial histologic diagnosis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1992;167(1):1-7.

- Thomas AM, Hickey M, Fraser IS. Disturbances of endometrial bleeding with hormone replacement therapy. Hum Reprod. 2000;15 Suppl 3:7-17.

- Harlow SD, Gass M, Hall JE, Lobo R, Maki P, Rebar RW, et al. Executive summary of the Stages of Reproductive Aging Workshop + 10: addressing the unfinished agenda of staging reproductive aging. Menopause. 2012;19(4):387-95.

Note: Medical and scientific information provided and endorsed by the Australasian Menopause Society might not be relevant to a particular person's circumstances and should always be discussed with that person's own healthcare provider. This Information Sheet may contain copyright or otherwise protected material. Reproduction of this Information Sheet by Australasian Menopause Society Members and other health professionals for clinical practice is permissible. Any other use of this information (hardcopy and electronic versions) must be agreed to and approved by the Australasian Menopause Society.

Content updated 25 January 2024